Why is supporting regulation so challenging?

As the author of a self-regulation curriculum, I hear from many people who are struggling to support clients in developing regulatory capacity. Parents, teachers, and therapists are all doing their best to support children in developing these important skills, but often what works for one doesn’t work for another. And what worked for us when we were kids isn’t working for kids now.

Almost everyone who reaches out wants to know what to do. But the answer to that question is complicated because self-regulation isn’t one thing that can be addressed with one set of tools and strategies. It is a complex, developmental capacity that takes many brain networks working together. It has foundations in basic physiological processes like sleep/wake cycles and neurological arousal; it develops through sensorimotor and relational experiences; and it is expanded through overcoming challenges using our body and our brain. Developmentally, all of that happens way before we can use a curriculum to “teach” self-regulation.

Self-regulation requires layers of support.

Here are some commonly described scenarios:

Therapists often share that they have taught a child to self-regulate using a curriculum, but the child is not able to use tools and strategies in a moment of dysregulation. The therapist has supported the child’s understanding of sensorimotor strategies, and they can repeat them with the therapist in a session, but in the real world regulation is still a huge challenge. In these situations, the child usually needs support in less cognitive ways. They need a different layer of support.

Therapists often report that they have a good rapport with a child and the child enjoys coming to therapy, but isn’t “willing” to engage in any therapist led activities and will only engage if they are able to choose the activity themselves. The child can attain a regulated state, but struggles to expand their regulatory capacity or adapt in the face of challenges. The tendency can be for the therapist to start teaching regulation strategies in explicit ways, but often my recommendation is to engage in play and everyday interactions in a way that stretchestheir regulatory capacity by providing their brain and body ways to practice self-regulation. This creates an embodied experience of regulation, rather than using didactic ways of learning.

And then sometimes a client actually is ready for lessons where they learn about their body and brain and can explore tools and strategies that work for them. But in a moment where they are dysregulated they may need us to shift our expectations and reduce the stressors to get back to a regulated state. The layer of support needed can change from moment to moment.

The variety of supports for expanding regulatory capacity is immense. What works for one child (or adult) will not work for another. What works for a child in one moment might not work for that same child in another moment.

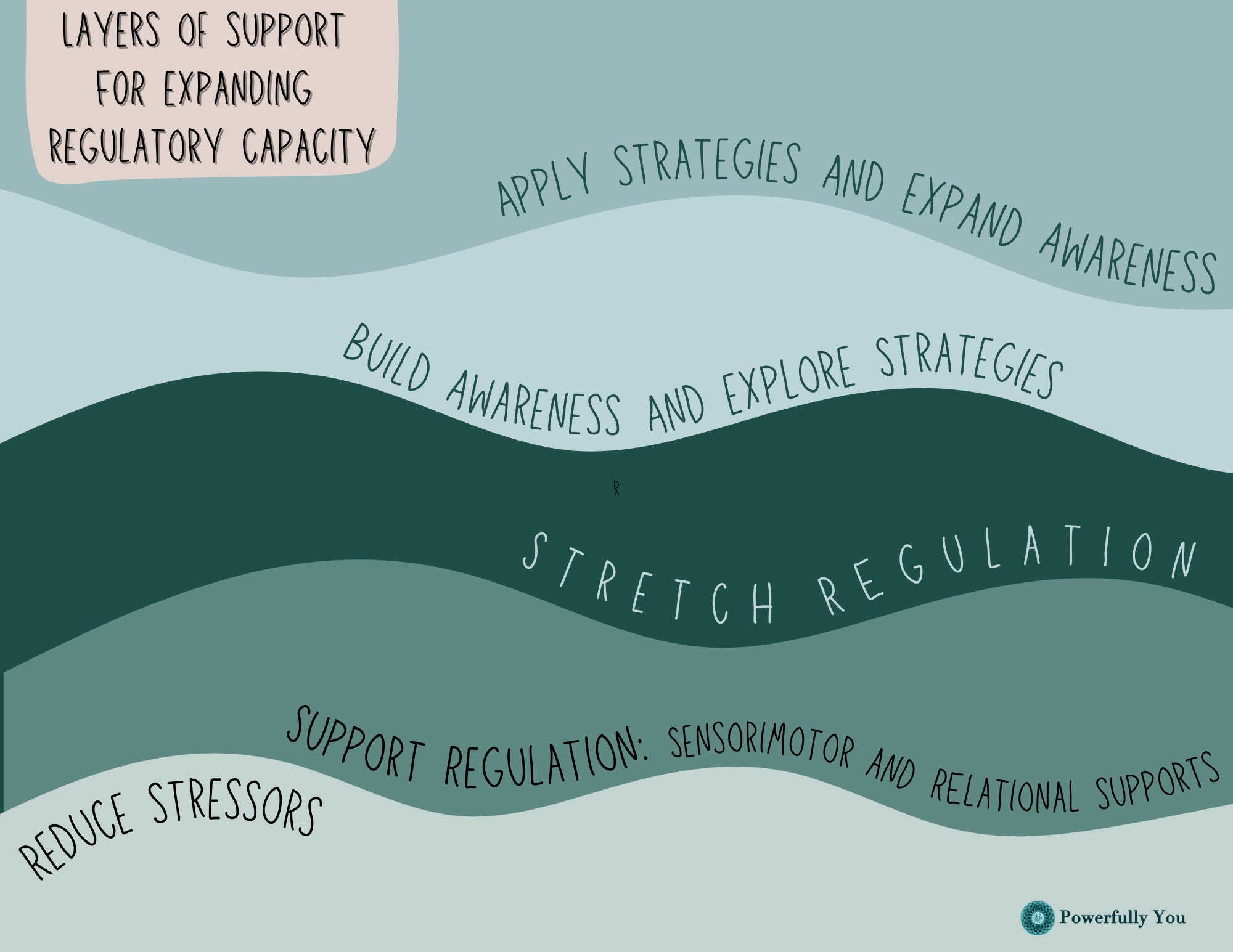

So what are the layers of support for expanding regulatory capacity? I have come up with the categories of: reducing stressors, supporting regulation with sensorimotor and relational supports, stretching regulation, building awareness and exploring strategies, and then applying strategies and expanding awareness.

Regulatory capacity is built through many, many experiences of receiving relational support (co-regulation) and sensory support provided to us by another. Adults expect infants to need sensory supports (movement, touch, deep pressure, positioning, oral motor supports, etc.) and relational supports to be regulated. Eventually, we expect them to need less support and become more “self-regulated”. But the truth is, as humans, we are never entirely self-regulated. We reach out to a trusted person when we have had a bad day and need to vent. We long for a hug or a pat on the back or an empathetic expression. Co regulation is always part of what we need to maintain our own regulation. Those moments of co regulation can often resource us just enough to allow us to use our previously established internalized regulatory strategies. Admittedly, sometimes we have to really dig deep and resource ourselves because co regulation isn’t available, but that takes a lot of energy and a lot of internal resources, and the capacity to do that relies on previous experiences of being co regulated.

Children (and adults) with developmental trajectories that are not on a predictable timeline often need more support for longer periods of their life. It can feel to us like they are “old enough” or have enough cognition to need less support, but their behavior shows us that they aren’t there yet. They have not internalized the regulatory strategies in a way that allows them to be accessible at times of dysregulation.

When we have these clients for whom dysregulation is still an ongoing issue it can be tempting to try to “teach” them strategies. We might want to build their awareness through discussions of “what should you do if…?”. We might want to talk about or explore strategies that could be helpful. But when their behavior is telling us that they are not embodying these strategies, we need to know how to shift to a different layer of support.

What are the layers of support for regulatory capacity, and how do we provide support in each layer?

Reducing Stressors:

Our first step in working with a child who is experiencing dysregulation or demonstrating big behaviors often needs to be recognizing triggers, reducing expectations, and decreasing stress. This can feel counterintuitive, because we want the child to be doing more than they are currently doing, not less. We might not want to lower the bar.

But acquiring new skills and engaging in self-reflection are tasks that take an incredible amount of energy and emotional resources. Self-regulation researcher, Dr Stuart Shanker, says “Seeing a child as 'capable of controlling his behavior if only he chooses to do so' only adds to our agitation and, as a result, the child's distress.”

Reducing stressors allows us to take a step back and provide the support needed to create “space” in the child’s nervous system for behaviors to eventually shift. When individuals are experiencing high levels of stress (which is almost always the case when we are seeing big behaviors) that space for possibility doesn’t exist in their nervous system functioning.

But it doesn’t mean that we always shift our expectations permanently. From my point of view, as a pediatric occupational therapist, we have options beyond accommodations and reduced expectations. We have the ability to support the nervous system, from both a bottom-up (less cognitive) and top-down (more reliant on cognition) perspective, in a way that allows regulatory capacity to expand. We will talk about that as we move into other layers of support.

This need to reduce stressors doesn’t just apply to individuals who aren’t ready for the other layers of support. It also applies to anyone in a moment where they are beyond their capacity to cope. Dr Shanker explains, “Stressors can change over time, but they can also change according to the mood or state that the child is in. So for the same child, what’s a stress in one moment might not be a stress in another”.

Psychotherapist Bonnie Badenoch says “Each of us is literally doing the best we can at any moment, given the state of our neurobiology and our level of support.” When we believe that about a child, and support them by reducing the stressors, we provide the best chance for thriving behaviors to emerge.

When we don’t reduce stressors, we can expect them to develop patterns of escalating behaviors or respond by shutting down. While shutting down can look like compliance in the short term, in the long run it does not expand our regulatory capacity, support higher level social and emotional skills, and wellbeing.

Supporting Regulation:

As a sensory integration trained OT this layer of support is often the focus of my interventions and supports. Sensory integration was first defined by Dr. A Jean Ayers as “the organization of sensation for use”. This broad description is deceivingly simple, as the process of sensory integration is incredibly complex. It involves the ways our brain processes sensations (through modulatory and discriminatory brain circuitry), how that results in motor output and skillful actions, and how those ways of processing sensation interact with regulatory capacity. In simplistic terms: sensory integration affects regulation, and regulation affects sensory integration.

Sensory integrative processing is also involved in affective processing through the sensory modulation functions. The sensory modulation circuitry in our brain judges each and every incoming sensation (of which there are millions in each second) as being positive or negative for us and codes it with positive or negative “affective valence”. This affective valence underlies our emotional experience and is the foundation for our motivation and social emotional capacities.

If all of this sounds like a foreign language or feels complex, it is. It is a specialized field of study and not all occupational therapists have received training in sensory integration and processing. Most know something about sensory strategies and sensory systems, but that isn’t the same thing as knowing how to evaluate sensory modulation and sensory discrimination functions.

One professional might say “I tried a fidget and some heavy work strategies and their behavior didn’t change” and conclude that “It isn’t a sensory issue”; but unless they have the knowledge to report on the sensory modulation and sensory discrimination capacities across sensory systems and how that interacts with regulatory capacity they cannot definitively make that conclusion.

This layer of support includes strategies and interventions that support sensory integrative functions, affective development, and motor development. This requires that professional be trained in sensory integrative processing assessments and interventions, interventions that support motor development, and relational approaches that support social and emotional development.

For example: A child who struggles with vestibular discrimination challenges would be identified through oculomotor testing and assessment of subtle motor patterns and coordination. An SI trained therapist doesn’t just observe “can the child see?” or “can they stand on one foot?”; rather they are looking at the quality of movement in these tasks and can report specifics about the way a child’s eyes move or the planes of movement a child engages in to allow for skillful use of their body. And they know how to address these sensory systems through playful interactions that allow the child to become more skillful and more precise in the way that their brain processes information.

A therapist who is trained in relationship-based interventions will consider how the caregiver can support their connection and sustained interactions with a child in a way that enables more complex social emotional capacities to emerge.

In this layer of support a therapist will consider the role of dynamic postural control and breath support, not by telling the child to sit up straight or take a breath, but by knowing the way that positioning and activation of motor patterns and sensory input will support breath. It takes eyes trained to see breath to facilitate this kind of support.

Often, a therapist trained in a sensory integrative approach is going to use specific approaches like: a deep touch pressure approach first described by occupational therapists Pat and Julia Wilbarger, or auditory interventions that support sensory integration, or body based interventions that address fascial and musculature restrictions. These trainings are specialty areas of practice that require additional training to implement, and many of these interventions are not well understood by therapists who have not received these trainings. They are not exposure based interventions but rather are respectful and supportive of the nervous system.

In my experience, this is often the most necessary and impactful layer of support that I provide, as an occupational therapist. Sometimes, when we support this level of function, we see progress in all levels of functioning: attention improves, communication improves, play skills and social emotional skills improve expand, self of self expands, and they experience an overall decrease in stress and increase in wellness. Because sensory integrative processing (including affective development) underlies all of these observable behaviors.

Finding someone to provide this layer of support is often imperative when a child struggles with attaining and maintaining regulation.

Stretching Regulation:

This layer is sometimes the hardest to describe. A child who is ready for this layer of support is able to sometimes attain and maintain regulation with minimal support, but their ability to maintain regulation in the face of a challenge is compromised.

Therapists and other adults are often tempted to start requiring a child at this level of development to tolerate increased expectations and meet adult driven goals. But there is a layer of support that we can provide that expands regulation, which is often still a fragile capacity for the child.

Therapists might say that the child who needs this layer of support has a “narrow window” of adaptability. They need things to be just right or they can’t maintain regulation.

There is often a temptation to start “teaching” this child about regulation. But that would be skipping a layer of support where we provide social emotional and motor challenges that expand their window of adaptability to stretch their regulation. When we stretch regulation, we make it more robust and we increase their ability to be regulated in a variety of situations.

But we don’t do that by arbitrarily increasing our expectations. We pick opportunities to challenge their arousal regulation, their ability to solve their own problems in connection with a trusted adult, and their ability to stay connected in general. We empower self regulation through connection and play based challenges.

The art of providing this type of support is something I learned by observing my early mentors, and through coursework in DIRFloortime®. Parents and caregivers can naturally provide this support through scaffolding challenges and “doing with, not for” kids.

Stuart Shanker says, “Stress is necessary for growth, but only when it is manageable.” In this layer of support we create a little bit of stress or join the child in a moment of stress and provide the support that makes it manageable.

Finding a therapist who can support you in knowing how to provide the “just right challenge” is imperative to stretching regulatory capacity and expanding the child’s adaptability in a way that respects the nervous system and their individual differences.

Building Awareness and Exploring Strategies:

When children are ready for this level of support, we can finally bring in some “teaching” of information about the brain and supporting strategies. We can talk about how things feel for that child, what works for them, how the brain and body work, and we can try things together. The adult will facilitate the child noticing how strategies and tools affect them. We can explore how we experience emotions and notice how thought based tools can be used to shift our thoughts.

This is where we can use a curriculum. We can do experiments. We can teach lessons.

But even here we are always thinking about the underlying regulatory skills and supporting regulation. We are not expecting the child to self-regulate in challenging situations, and we are providing proactive supports for regulation. Co regulation is still a frequently used strategy.

Applying strategies and expanding awareness:

Finally, we can talk about the layer of support where a child starts: using strategies proactively, observing how they feel in the moment some of the time, reflecting on times that they struggled after those moments are over. But still…they will require frequent co-regulation and support.

It is common for adults to think that the goal is for the child to be self-regulated.

While it may seem like some adults move away from needing co-regulation, that is not the most adaptable way to regulate and doesn’t support social and emotional wellness in the long run. That could be the topic of another blog (or 2-day course!) so for today I will leave it at that.

We ALL continue to require frequent co-regulation and support for our lifetime.

I hope this introduction to the layers of support serves as a catalyst for you to think about the ways you are providing support, and maybe the ways that you aren’t providing support. Supporting self-regulation is challenging and we ALL need support for our own regulation and for building knowledge.

We are better together.

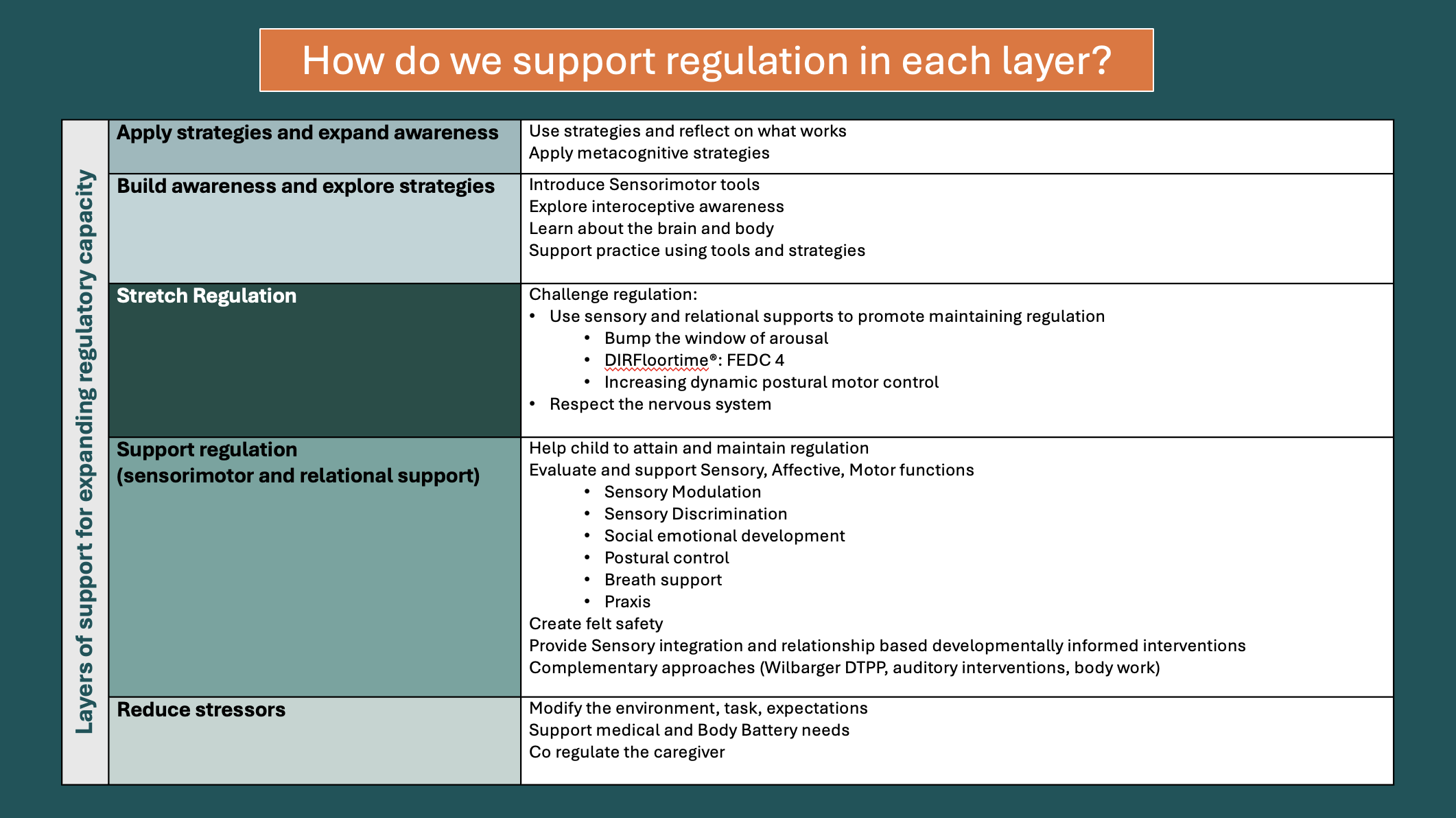

This chart represents what a professional can do to support function in these “layers of support.”